Municipal elections in Canada do not command the same level of respect and trust as elections at the district or provincial levels. For example, in Ottawa in 2018, fewer than 43% of registered voters cast a ballot. Experts often attribute this to insufficient information and a lack of confidence in the candidates.

Yet there was a time when residents’ attitudes were quite different. Ottawayes takes a look at the story of elections in Bytown, which later became Canada’s national capital.

Problems Facing Communities and Their Solutions

Delving into the history of local elections, it’s important to note the desire of residents to create independent municipal governance that would answer to local taxpayers. This gave rise to tensions that ultimately split communities.

- British Loyalists: After the American Revolution, they fled northward. Raised in New England, New York, or Pennsylvania, they arrived in Canada with certain democratic practices. Nevertheless, many believed that holding free elections at any level—especially local—posed a threat to peace and order, and thus favoured officials appointed by the Crown.

- Lower Canada, which adhered to French civil codes and traditions.

- Upper Canada, which followed British common law. From 1791 onward, it was home to English-speaking supporters of the British Empire.

Among those who resisted democratic reforms and tried to prevent their adoption in Canada was General Simcoe, the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. It was a serious challenge: Canada and its provinces needed decades to establish true democracy.

The Right to an Elected Police Board

In 1832, Brockville obtained the right to form an elected police board. This was the first fracture in the authoritarian structure and brought Canada closer to democracy. Other cities quickly followed suit. Here are a few key historical milestones:

- In 1834, the city of Toronto (formerly York) held direct elections for mayor and aldermen.

- The following year, a new act transferred municipal powers to elected councils (until then, these had been exercised by magistrates).

- In 1838, during the uprisings, democratic reforms were revoked.

In 1839, Lord Durham published a report explaining the causes of the uprisings and proposing possible solutions. He stressed the need for a strong system of municipal institutions throughout the province.

The District Council Act

Passed in 1841, the District Council Act was effectively a compromise between:

- Conservative forces, eager to maintain local control,

- and radical or reform-minded groups, striving for 100% local self-government.

How These Changes Affected Bytown: The First Election

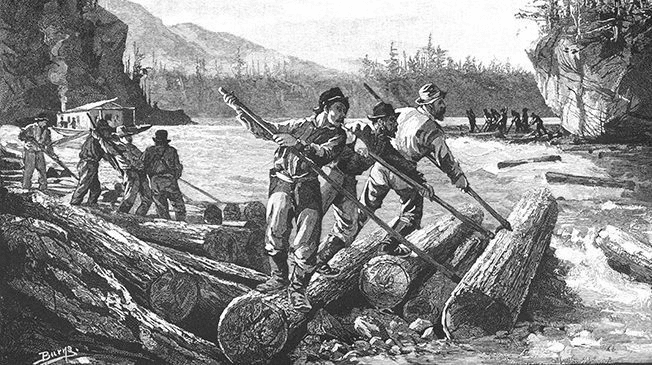

It’s worth noting that the small settlement of Bytown, founded in 1826 by Lieutenant Colonel By (the architect of the Rideau Canal), also developed robust mechanisms for local self-government. Initially established as a military settlement, Bytown gained a superintendent for the surrounding district in the 1830s.

In 1847, Bytown was given a new status and was split into three wards: North, South, and West. That September, the town held its first election for seven aldermen: three from the West Ward and two each from the North and South Wards. The North and South were predominantly working-class, with many French and Irish Catholics, while Upper Bytown was home to the English-speaking Protestant elite.

Here are some fascinating historical details about that first election:

- Only men over the age of 21 could vote.

- A mere 878 men came out to cast their ballots.

- Eligible voters had to own property valued at no less than 30 pounds sterling, rent land at an annual rate of at least 10 pounds, or occupy a house rented at or above that annual amount.

- Voting was open (secret ballots only came after the Baldwin Act, two years later).

- Open voting was highly valued, whereas secret ballots were seen as cowardly and politically hypocritical.

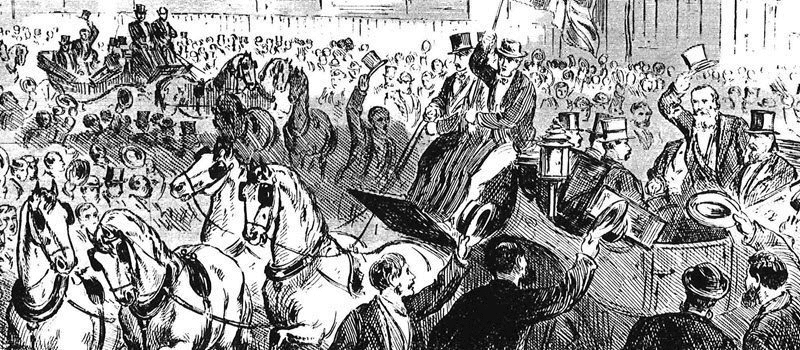

During its first session, the newly formed council—consisting of seven aldermen—chose John Scott as Bytown’s first mayor.

Ottawa’s Second Election

The next election took place in April 1849, because John Scott decided not to run. A Tory, Robert Hervey, was elected mayor. He faced serious challenges: on behalf of Queen Victoria, the Act that incorporated Bytown was officially revoked. This came as a shock, leaving people uncertain about the future. Later, municipal affairs were reorganized, and in January 1850 the town held new municipal elections.

John Scott, returning to politics alongside the majority of reform-minded council members, was appointed mayor of Bytown for a second time. On January 1, 1855, the city was officially registered under its new name: Ottawa.

Fascinating Facts About Voting in Those Days

Having the right to vote was, in reality, a privilege. We’ve already mentioned that only men over 21 with sufficient property could vote, but there were other considerations as well:

- Voters’ lists were compiled, and eligible names moved among various provinces and the federal government. In some locales, certain citizens could be disqualified and thus lose their voting rights.

- Beginning in 1869, men from First Nations were allowed to vote if they renounced their Indian status. Notably, men and women from Indigenous communities who served in the First and Second World Wars also became eligible to vote, and in 1960 all Indigenous people received full voting rights.

- Métis men could vote if they met specific criteria. The first Métis was elected to Parliament in 1871, and in 1918, women—including Métis women—gained the right to vote.

- Inuit were granted voting rights only in 1950; before that, they were excluded from elections.

- Throughout 1917 and again from 1938 to 1955, those who refused military service could lose their voting rights.

- People born in “enemy nations” or speaking an “enemy language” were barred from voting during the First and Second World Wars.

- Black Canadians who satisfied the basic criteria (a man over 21 with property) could vote at the federal level.

- For many years, election officials, judges, and civil servants were ineligible to vote; this finally changed in 1988.

- Citizens with developmental disabilities had been stripped of voting rights from 1898 to 1993, while incarcerated individuals were denied voting rights until 2004, regardless of the length of their sentence.

Such is the story of the first elections in Bytown and, eventually, in Ottawa. Residents fought for democracy and for the right to vote itself. It’s worth remembering this as we freely cast our ballots in the modern world.