Aircraft became an integral part of World War I. Aviation technology advanced rapidly, and planes were used for aerial combat, ground attacks, and reconnaissance missions. Ottawa Yes explores the development of Canadian aviation and the role Ottawa played in this process.

The Era of World War I

Approximately 20,000 Canadians served in British air services:

- The Royal Flying Corps,

- The Royal Naval Air Service,

- The Royal Air Force.

More than 1,400 of them were either killed or wounded in action. At the time, Canada did not have its own air force. In 1914, the country established the Canadian Aviation Corps, consisting of a single aircraft, but it was soon disbanded without ever being used in combat.

By 1924, Canada established a permanent military air force, known as the Royal Canadian Air Force.

At the beginning of World War I, Canadian government officials were skeptical of the usefulness of aircraft in combat. However, France, Germany, and Britain were already exploring ways to use airplanes effectively in warfare. Aircraft underwent rapid technological evolution and became a crucial factor in the outcome of battles.

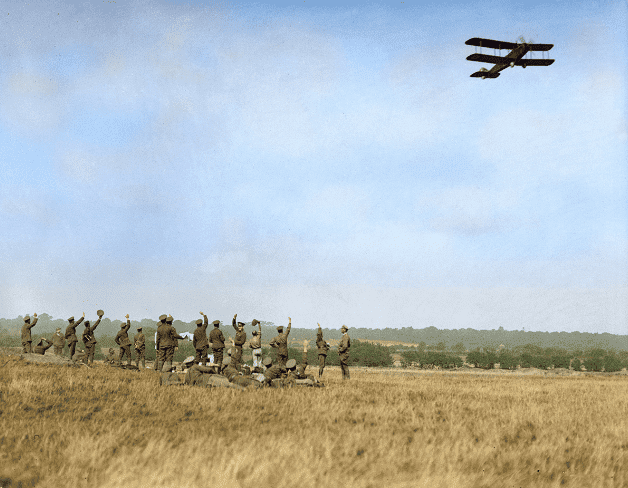

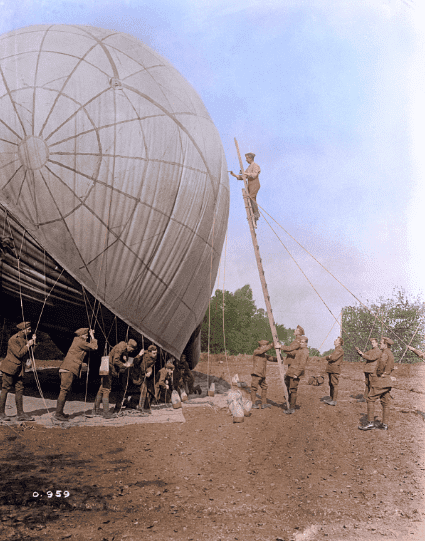

Aerial Reconnaissance

Aerial reconnaissance played a key role in military strategy. One of the earliest examples occurred in September 1914 when reconnaissance flights revealed the division of German armies during their march to the Marne River. This intelligence allowed the Allies to counterattack and push the German forces back, halting their advance.

Aircraft became a valuable tool for gathering intelligence about enemy formations. Both Allied and German forces suffered heavy losses, leading to a stalemate.

Air warfare during this period involved:

- Shooting down enemy aircraft,

- Photographing enemy positions,

- Providing crucial intelligence to commanders and gunners.

Although fighter planes often receive the most attention in books and films, reconnaissance aircraft played the most critical role in gathering intelligence.

“Dogfights” in the Sky

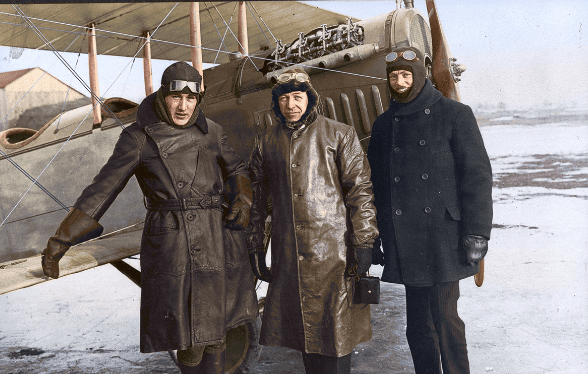

Early pilots initially used shotguns, pistols, and rifles to attack enemy aircraft. Some even dropped metal darts or small bombs. Many pilots perished in air battles or during landings due to rough and uneven airstrips.

Canadian pilots, many of whom were from Ottawa, had the advantage of quality education and strong social backgrounds. They could afford private flying lessons and join the Royal Naval Air Service or the Royal Flying Corps.

The demand for pilots was so high that training periods were drastically shortened, leaving many ill-prepared for combat. As a result, inexperienced pilots were often quickly shot down by seasoned enemy aces.

New Training Schools

The war necessitated the rapid expansion of pilot training programs. Flight schools were established across Canada. One of the first was in Toronto, which graduated 129 pilots. In early 1917, another major school opened in Camp Borden, Ontario, featuring a structured training program. This ensured a steady flow of trained pilots for the frontlines.

During the harsh winters of 1917-1918, many Canadian flight schools had to close due to extreme cold. Training was moved to Texas, where Canadian and American pilots trained together. Approximately 3,135 pilots completed training, with 2,500 being deployed overseas.

Canadians Who Made Their Mark on the Frontlines

Two notable Canadian aviators who excelled on the Italian front against German and Austrian forces were William Barker and Clifford MacKay “Black Mike” McEwen.

William Barker

Barker became one of the most successful reconnaissance pilots. After returning to Europe, he fought a legendary solo battle against more than ten German fighter planes. Despite sustaining three serious injuries, he survived. He was awarded the Victoria Cross and numerous other medals, making him the most decorated aviator in Canadian history.

Barker died in 1930 in Ottawa in an aviation accident while demonstrating a new trainer aircraft. His plane crashed onto the frozen Ottawa River. He was buried in Toronto, where thousands attended his funeral.

Clifford “Black Mike” MacKay McEwen

McEwen earned his nickname due to his ability to tan deeply. He was one of Canada’s most successful fighter pilots and later became a flight instructor in Ontario. His contributions to aerial warfare in both World Wars were immense. He received numerous awards, including the Order of the Bath from King George VI. He passed away in Toronto and was buried in Pointe-Claire, Quebec.

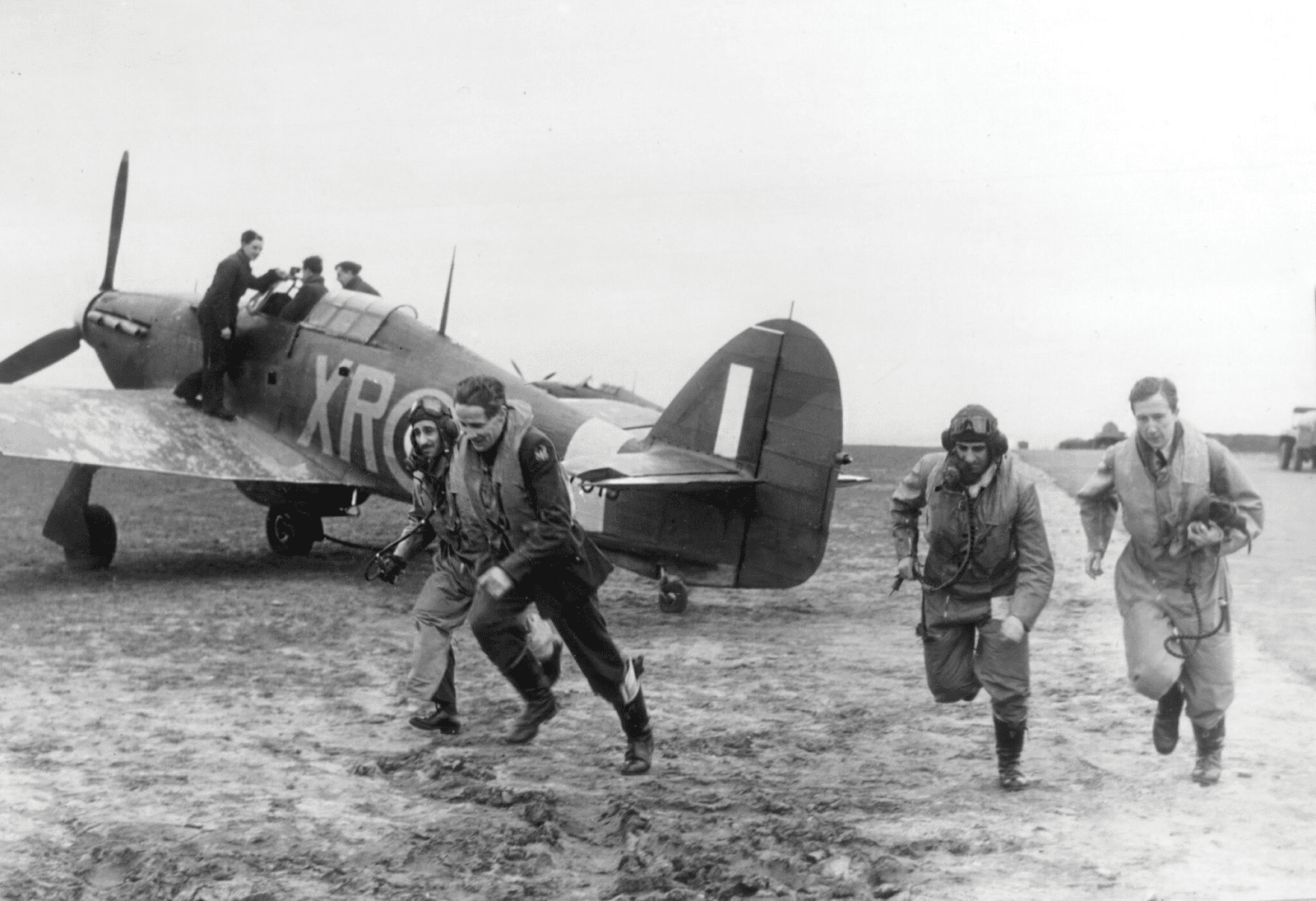

The Battle for the Skies

In 1916-1917, the Germans had numerical superiority in the air, but they still suffered a series of defeats. By late 1916, German forces dominated the skies, but this advantage gradually diminished.

Canadian pilots, known for their skill and determination, secured many victories. One of the most remarkable Canadian aces was Donald MacLaren, an Ottawa native. During World War I, he achieved 54 aerial victories in less than eight months—a remarkable record.

Pilots of this era were called “knights of the air,” but their training was brutal. They faced immense physical strain. In winter, they wore fur-lined suits, flying goggles, and coated their skin with whale oil to prevent frostbite. Despite these precautions, they still suffered from extreme cold and oxygen deprivation, which slowed their reflexes and often led to fatal consequences. Many pilots experienced severe weight loss and ulcers. Alcohol was one of their few coping mechanisms.

The Harsh Reality

Pilots dreaded the possibility of burning alive inside their aircraft. To avoid this horrific fate, they carried revolvers or pistols to take their own lives if necessary.

While German pilots were issued parachutes, the British military refused to provide them. This decision resulted in unnecessary loss of life.

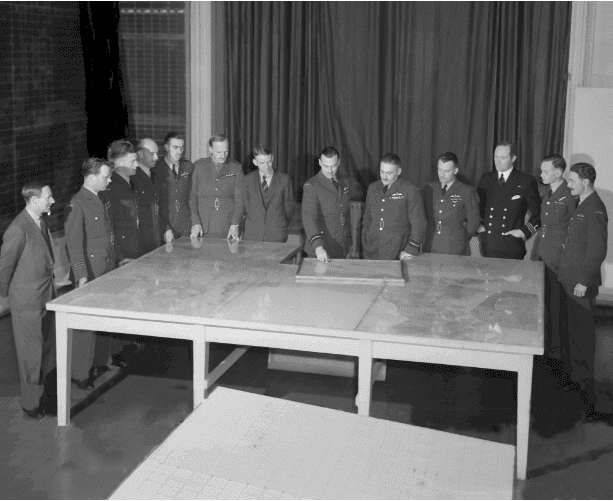

The Royal Canadian Air Force

Canadians had a reputation for being skilled and resilient pilots. Some of the most famous include Billy Bishop, William Barker, Raymond Collishaw, and Donald MacLaren. Despite this, Ottawa did not have a national air service at the time. A small Royal Canadian Naval Air Service was established in 1918 but was later disbanded.

Senior Canadian officers advocated for an independent Canadian air force during the war. However, their efforts were blocked by Canadian politicians, leading to missed opportunities.

On April 1, 1924, Canada finally established the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF).

Experts estimate that over 20,000 Canadians served in the British air forces during World War I. The Peace Tower’s Memorial Chamber in Ottawa records 22,181 Canadian war casualties.

More than 1,400 Canadian airmen were killed, while those who survived returned home as veterans. Many struggled to reintegrate into civilian life. However, their aviation skills proved valuable during World War II, when they contributed to mapping Canada’s northern territories and delivering mail to remote communities.

The legacy of Canadian pilots from World War I continues to shape the nation’s air force and aviation history today.