Historical records and firsthand accounts take us back to September 3, 1939, in Ottawa. A peaceful time, peaceful people—Labour Day weekend. It was the last weekend of summer, yet across Canada, people were not celebrating. Instead, they were listening to the news. Everywhere, people were gathered around their radios. Ottawa Yes explores Ottawa’s wartime history and how its residents responded to one of the most challenging times in history.

September 3, 1939

This date became deeply etched in the memory of Ottawans. At 6 a.m., citizens of Ottawa learned that Great Britain was now at war with Germany. The British ultimatum delivered to the Reich’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs had gone unanswered. This was a direct response to the German army’s invasion of Poland.

Although the news did not come as a surprise to Ottawans, no one could truly prepare for what was coming. The war drums had been beating for some time, growing louder each day. Panic and fear among ordinary citizens escalated.

On top of the invasion of Poland, Germany and the Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact in mid-August, further fueling tensions.

How Did Ottawans React to the News?

There were no cheers—only sombre faces. That Saturday morning, families went to church to pray. Then, they turned their radios back on to hear more updates.

Ottawans listened to King George VI’s address and the call to remain at home while the military took action. Many people cried, as only months before, the royal couple had visited Ottawa.

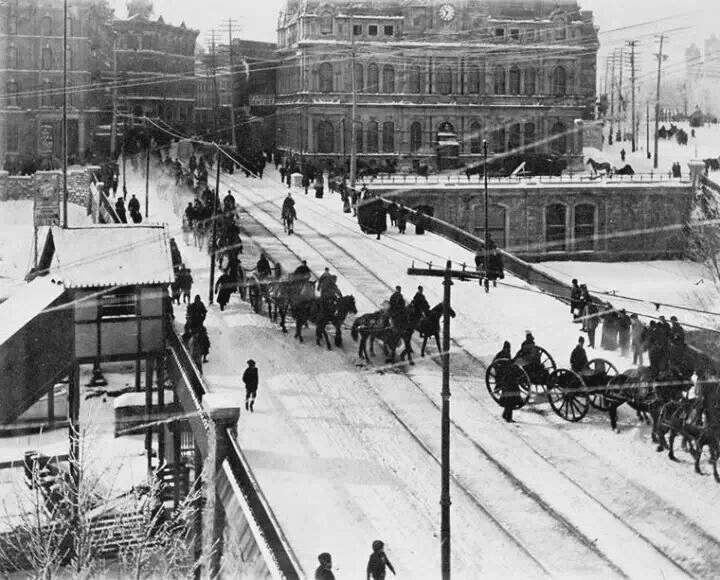

At 10 a.m., an emergency Cabinet meeting took place in the Privy Council Chamber on Parliament Hill (East Block). On Sparks Street, hundreds gathered outside the Ottawa Citizen office, eager for the latest updates.

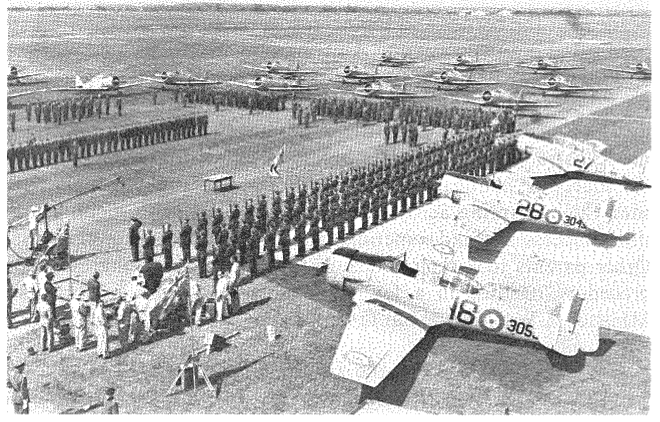

Ottawa’s troops were mobilized, and artillery units moved toward Lansdowne Park. Security was deployed at utilities and milk processing plants to prevent possible sabotage. Around the city, posters called for men of conscription age to report for duty. Men were expected to appear at Cartier Drill Hall by Monday at 9 a.m. Posters were recruiting clerks, turners, mechanics, saddlers, and men for the RCASC.

At around 2 p.m., Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King left the meeting. A crowd gathered at the entrance, applauding as he emerged. He promised cooperation with Britain and urged everyone to unite for a common cause.

Was Ottawa at War?

Ottawa’s leading newspapers emphasized that Canada was now in a state of war. However, the reality was more complex. After the Statute of Westminster (1931), Canada had gained autonomy as a dominion within the British Empire. This meant that when Britain declared war, Canada was not automatically bound to join.

Prime Minister King refrained from making any immediate declarations, waiting instead for parliamentary debates. Meanwhile, the United States had enforced the Neutrality Act, banning arms sales to warring nations.

Interestingly, the German consulate in Ottawa was located on Wellington Street, in the Victoria Building. Externally, everything seemed unchanged, yet German diplomats were destroying confidential documents and preparing for an urgent departure.

For instance, German Consul General Erich Windels, who had been in Ottawa since 1937, received no official instructions from his superiors. Nonetheless, his residence, like the consulate itself, was placed under surveillance.

Ottawa’s First War Casualties

Every war brings losses, and Ottawa was no exception. On the same day Britain declared war, Ottawa experienced its first wartime tragedy. Pilot Ellard Cummings, whose parents lived on Spadina Avenue, was killed in action. He and his Scottish gunner were among the first casualties. Unfortunately, he would not be the last. His parents received the heartbreaking news the following day.

Hours later, a German U-boat sank the SS Athenia, a 526-foot passenger liner. This was the first civilian ship deliberately targeted in the war. Onboard were 1,103 passengers, including 315 crew members. Among them were Canadians, Americans, and British citizens trying to return home before the full-scale war erupted. Over 20 people from Ottawa or with close ties to the city were aboard.

Despite rescue efforts, 98 passengers and 19 crew members perished. Survivors were picked up by the Southern Cross (Swedish yacht), the Norwegian tanker Knute Nelson, and the American freighter City of Flint. They were then transported to safety in Scotland and Ireland.

The attack on SS Athenia was a war crime. The U-boat commander, Fritz-Julius Lemp, failed to allow the passengers to escape safely and did not provide assistance to survivors. Later, it was revealed that the sinking had been a mistake, which cost many lives. The German Navy covered up the incident, ordering false entries in the ship’s log. The truth emerged only during the Nuremberg Trials after the war.

Ottawans anxiously called local newspapers, desperate for updates on their loved ones. Survivors shared heroic accounts of men giving their life jackets to women, sacrificing themselves so others could live.

Canada Joins the War

On September 10, 1939, Canada, including Ottawa, officially joined the Allies in the fight against Nazi Germany, alongside Great Britain, New Zealand, Australia, and other members of the Empire.

The End of the War

On May 7, 1945, the Act of Capitulation was signed, and newspapers announced the victory. Nazi Germany had been split in two, and on May 1, news broke of Hitler’s death.

It took over 12 hours for the good news to reach Ottawa. Some questioned why the city was not already celebrating—but that was quickly remedied.

It is easy to picture the scene: A young man ran through the streets, shouting, “It’s over!” Shopkeepers and passersby picked up the chant. At first, people could not believe it—after five years, eight months, and six days, the war in Europe was finally over.

Victory Celebrations in Ottawa

First, students from local colleges poured into the streets after being dismissed by their teachers. By midday, even usually reserved government workers had joined in. For once, daily responsibilities and worries were forgotten, replaced by waves of patriotic excitement.

On Parliament Hill, over 10,000 students gathered in front of the Peace Tower. The city erupted in joyful noise—bagpipes, whistles, sirens, and church bells rang out.

Fireworks lit up the Rideau Canal, and Allied flags were raised. On McLaren Street, residents burned an effigy of Hitler to the cheers of onlookers. The celebrations lasted well into the night. No one wanted the night to end.

The official blackout ended, and for the first time in years, Ottawa’s citizens could walk freely under the glow of streetlights, finally experiencing the joy of peace once more.